Summary

Plastic, and subsequent microplastic pollution is a known hazard in our seas, but its full cycle from source, through transportation, to fate is less discussed. This infographic aims to introduce microplastic pollution, and its life cycle, to early secondary school students to engage them in the topic of plastic pollution and encourage them to become active and thoughtful citizens.

Transcript

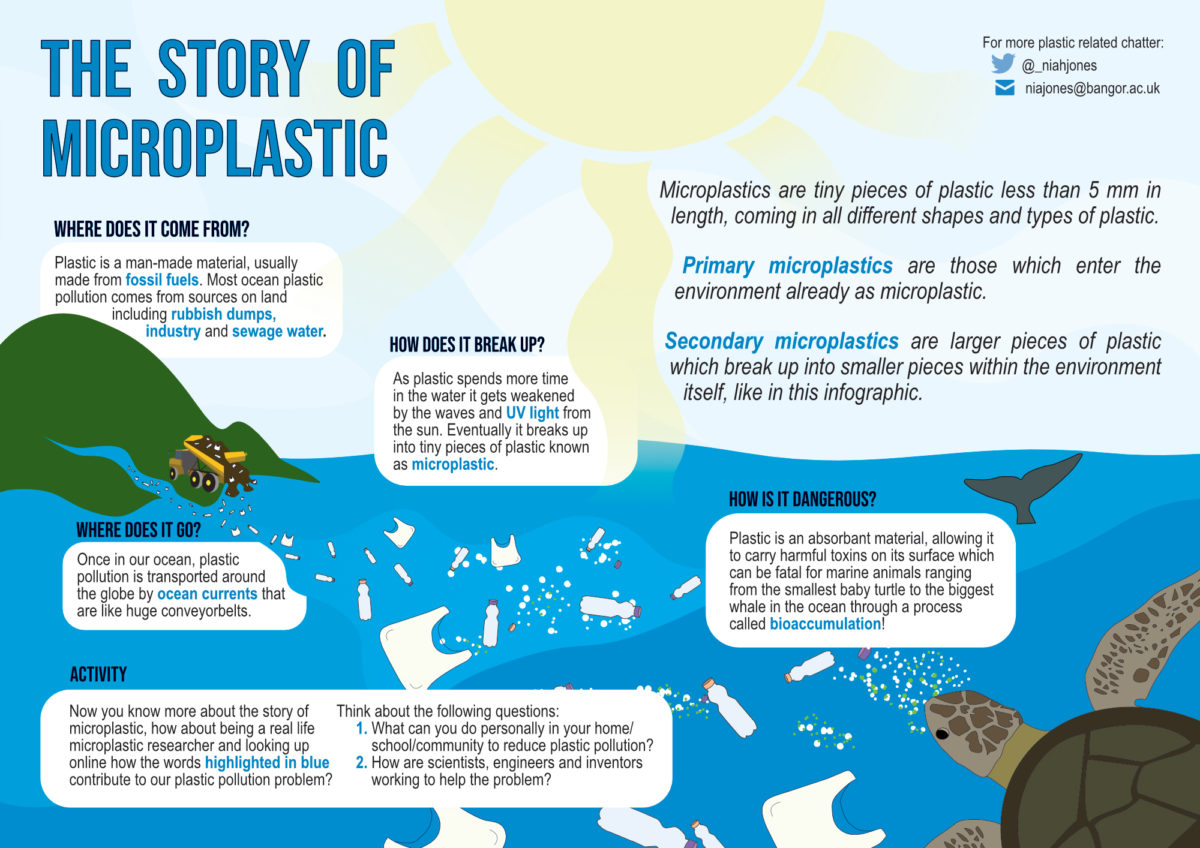

Microplastics are tiny pieces of plastic less than 5 mm in length, coming in all different shapes and types of plastic. Primary microplastics are those which enter the environment already as microplastic. Secondary microplastics are larger pieces of plastic which break up into smaller pieces within the environment itself, like in this infographic.

Where does it come from?

Plastic is a man-made material, usually made from fossil fuels. Most ocean plastic pollution comes from sources on land including rubbish dumps, industry and sewage water.

Where does it go?

Once in our ocean, plastic pollution is transported around the globe by ocean currents that are like huge conveyorbelts.

How does it break up?

As plastic spends more time in the water it gets weakened by the waves and UV light from the sun. Eventually it breaks up into tiny pieces of plastic known as microplastic.

How is it dangerous?

Plastic is an absorbant material, allowing it to carry harmful toxins on its surface which can be fatal for marine animals ranging from the smallest baby turtle to the biggest whale in the ocean through a process called bioaccumulation!

Activity

Now you know more about the story of microplastic, how about being a real life microplastic researcher and looking up online how the words highlighted in blue contribute to our plastic pollution problem?

Think about the following questions:

- What can you do personally in your home/school/community to reduce plastic pollution?

- How are scientists, engineers and inventors working to help the problem?

Nia Jones

Nia is nearing the end of the first year of her PhD and is concentrating on the mechanisms that govern microplastic transport within our coastal systems and shelf seas. By integrating hydrodynamic modelling, particle tracking and in-situ measurements she hopes to estimate local microplastic budgets and investigate regional sources and sinks to better understand our plastic pollution problem. With a keen interest in science communication and outreach, Nia hopes to engage as many people as possible in microplastic research.

Email: niajones@bangor.ac.uk

Twitter: @_niahjones

Organisation: Bangor University